London’s Cultural Spaces: Data and Impact

27 September 2023

The events of the past few years had a profound impact on London’s cultural landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, Brexit, supply chain disruptions, inflation and the cost-of-living crisis put cultural spaces in London under great stress.

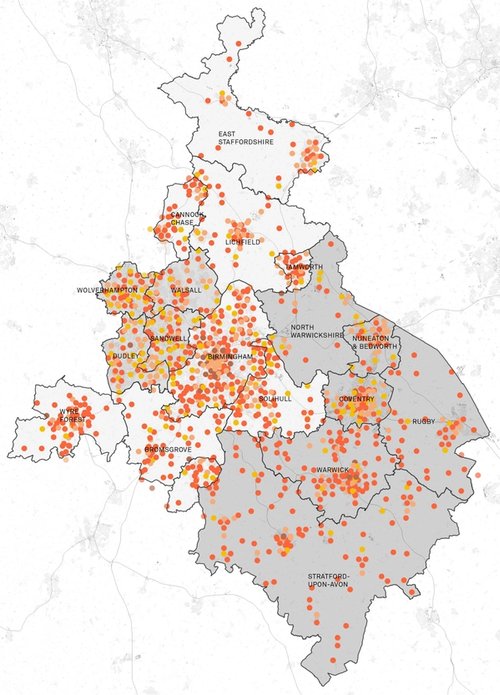

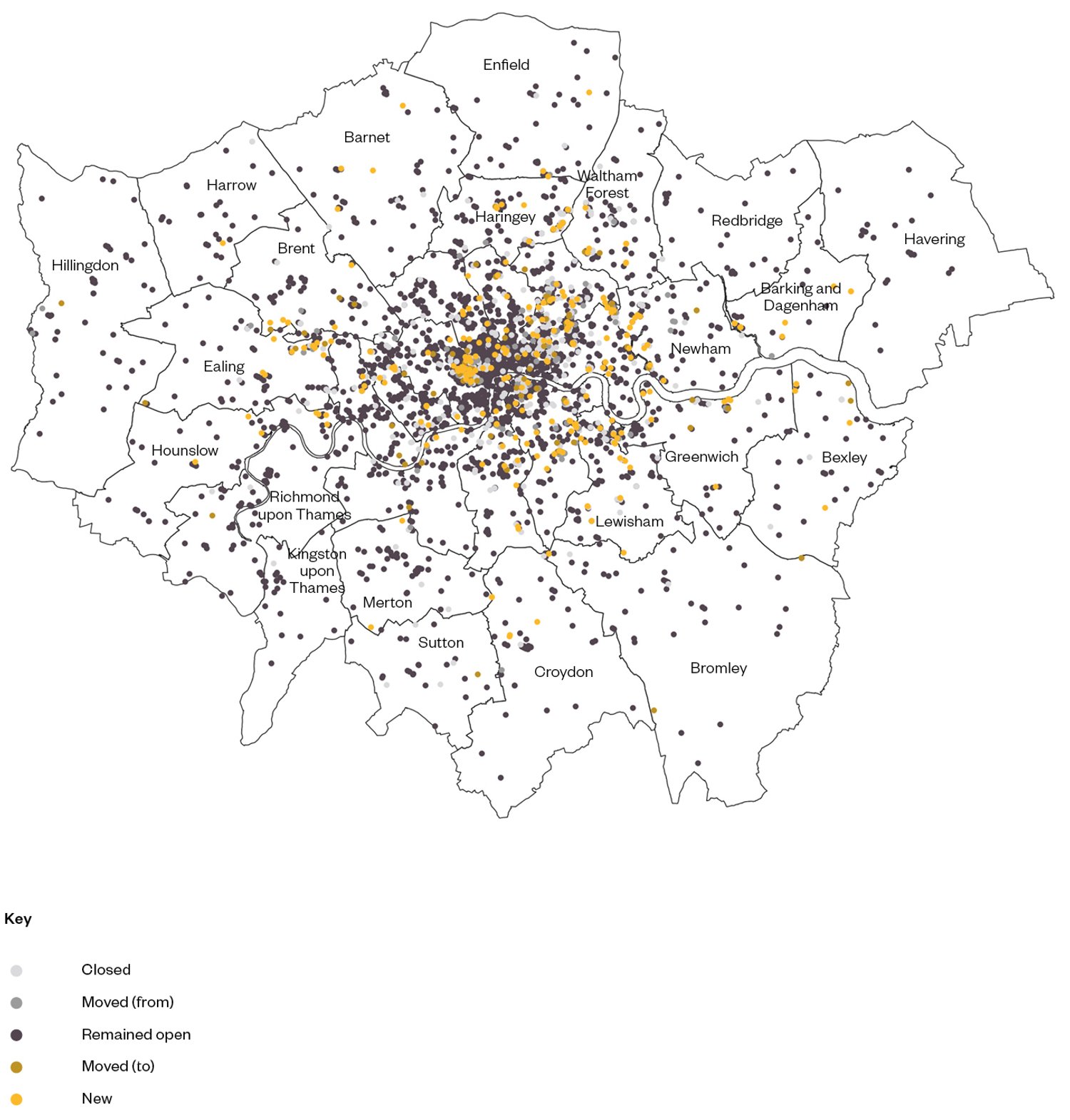

A study, commissioned by the Mayor of London and led by We Made That, provides an overview of the state of cultural spaces in London nearly three years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It draws on an update of London’s Cultural Infrastructure Map and a survey of cultural spaces. The update of the cultural infrastructure map reveals the extent to which new cultural spaces opened and existing cultural spaces closed or moved over the past years. In addition, the survey shows nuanced information about the financial situation of the organisations that provide space for culture in London, uncertainties about their future, issues of tenure security, or the extent to which cultural spaces were able to access financial support during the pandemic.

The evidence and findings from this study support further intervention to keep London at the top of its creative game and ensure there are cultural opportunities in every corner of the capital. It found:

- 2% fewer cultural spaces in London now than in 2018

- 31% spaces face tenure insecurity

- 59% spaces are in worse financial situation after the pandemic

- 5% more open workspaces now than in 2018

- 3 in 4 spaces are optimistic about still being open in 5 years

- 3 in 4 spaces accessed COVID-19 funding

You can read the key findings of the study here.

London’s Cultural Infrastructure Map update 2022

We commissioned Justinien Tribillon, an urbanist, writer and academic whose research focuses on infrastructure, cultural policy, migration and the politics of technical artefacts to reflect on our findings.

Multidimensional crisis threatens the future of London’s creative industries

It is rare to begin a policy document by quoting Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II speaking Latin. But since the previous edition of the Greater London Authority’s Cultural Infrastructure Map, the city’s cultural sector has truly experienced two anni horribiles. Not even addressing the lives lost to Covid, the impact on creatives in London has been profound, and multi-dimensional.

There is another, more creeping dimension to the initial crisis induced by Covid. Artists’ and creatives’ professional activities are more than regular jobs providing an income. Often, it is also their calling, their lives. Deemed ‘non-essential workers,’ with no access to their workspaces and deprived of new commissions, they have watched their industries not only shut down but collapse. The negative impact it has had on institutions and individuals’ mental health, well-being, and confidence for the future is massive. This malaise will continue unfolding in the years to come.

This is a key element to understanding the impact of Covid: it is just getting started.

Yes, lockdowns have stopped and Covid has become a new flu-like disease for most of us. Theatres, cinemas, workshops, dance studios, galleries, clubs, and museums have reopened. But the general anxiety, and the economic uncertainty it has generated, will linger, and potentially gain momentum in the coming years. In fact, the real threat lies ahead: venues for cultural production and consumption are concerned that they have survived temporarily thanks to extraordinary subsidies delivered by national and local governments. As the artistic director of an East London theatre interviewed for this study explained: ‘During Covid, we were all f*****. But there was some confidence that the Government would do something, otherwise, all cultural institutions in the country would go bankrupt.’ But these subsidies have dried up, and yet we are far from being ‘back’ to a pre-pandemic situation. There is no business as usual. Normality has been redefined, and what we knew before will never come back.

Shortages due to supply chain disruption, inflation, the impact of the war in Ukraine and the effect of Brexit, have complicated matters further and compromised the future of many cultural spaces in London — without forgetting these new threats arrive after years of budget austerity.

These phenomena are intricate and entangled. It is difficult for the respondents to the survey and the interviewees to pinpoint precisely what caused what. Indeed, Brexit, Covid or Russia: to identify who, or what phenomenon is to blame here is not relevant to our study. The rising cost of supply and energy prices have a direct, immediate, negative impact on cultural spaces in London. If a large share of respondents indicated they have confidence they will still operate in London five years from now, the range, diversity, and intensity of the services or programmes will be impacted. Cultural spaces catering to the most fragile, underrepresented populations are the first to close, with only 39% of minority ethnic led spaces confident they will be operating in London five years from now. Interviewees also declared they will have to decrease the number of plays they stage by 30% in order to cope with rising costs and decreased revenues from ticket sales. One can fathom the knock-on effect: fewer artists commissioned, fewer sets built, fewer drinks and food sold in local pubs and restaurants, a depleted cultural offer for Londoners, and a lessened cultural life for the city.

Creatives in London are on edge, they are tired, and burned out. The forced halt imposed by Covid has provided an opportunity to reflect on one’s professional choices. Many, including some we interviewed for this study, promised themselves they would change the way they work in order to tackle unhealthy work patterns and toxic practices in their industries. No more gigs back-to-back to make ends meet, to stay afloat, to exist in the industry and in London. But after such a long time without work, they jumped right back into a pace even more exhausting than before: because they desperately needed the cash, because they wanted to show their peers they had not lost it in an environment with less work on offer, and increased competition. Cultural spaces surveyed explicitly or implicitly explained they will pass on the increased costs of materials, energy, and inflation to their users. For spaces of cultural consumption, it might result in more expensive tickets for instance, but also fewer programmes. For spaces of cultural production, it will be passed on to artists and creative workers in the form of rent increase for instance.

Artists and creative workers are leaving the city. Factors such as cost and quality of life, toxic work practices, and the increased acceptability of remote working, are detrimental to London. It is still very difficult to assess how many creatives are taking the decision to leave the city, but the trend is felt widely. It is difficult to attract and/or retain workers across a range of roles that are critical to London’s cultural sector, from talents to front-of-house, management roles to baristas.

This ‘everything-but-London’ trend is also felt at the national level. There is a clear drive to invest everywhere but in London, which is already concentrating so many of the country’s top cultural institutions. Interviewees for this study clearly indicated that their funding partners are looking to invest outside the capital city. The latest figures released by the Arts Council on their National portfolio grants illustrate this point clearly. The share of funding awarded to London institutions in comparison to the rest of the country decreased from 41% in 2018–2022 to 34% scheduled for 2023–2026. The overall figure is set to decrease by 8% from just above £662 million to £608 million. Industries, foundations, and public bodies are putting their money outside of London while creatives are leaving to seek an improved lifestyle, better housing conditions, vaster more affordable studio spaces, etc.

It would be dangerous to consider the current concentration of world-class institutions and the crowd of creatives that come here to study, work and invent with them, a given. Institutions and individuals are slowly but surely leaving London. London needs to urgently challenge the self-confidence that it will always be the country’s and one of the world’s centres for culture.

Covid, as with all crises, came with its opportunities. We saw public and private institutions offering funding with little or no strings attached in the forms of open briefs, enabling creatives to challenge the established frameworks. NDT Broadgate is one of those radical examples that bloomed during Covid, a large completely free rehearsal and artists’ development complex opened from August 2021 to July 2022. But why are radical solutions only temporary ones? Why is it that we only dare to imagine the right solutions— in this case, free studios and workspaces for artists—when there is no risk they will become permanent?

We have entered a period of permanent crisis. We need to invent permanent radical solutions to support London’s cultural spaces and all stakeholders of London’s cultural life.